Thanks to the efforts of one Parsons High School junior, members of the C.A.M.P. Club and other students had the opportunity to learn more about acclaimed lawyer and social justice advocate Bryan Stevenson and his Equal Justice Initiative (EJI).

Students at PHS become familiar with Stevenson’s work through his book Just Mercy, in which he shares stories of freeing people who were wrongfully convicted or unfairly sentenced—many of them on death row.

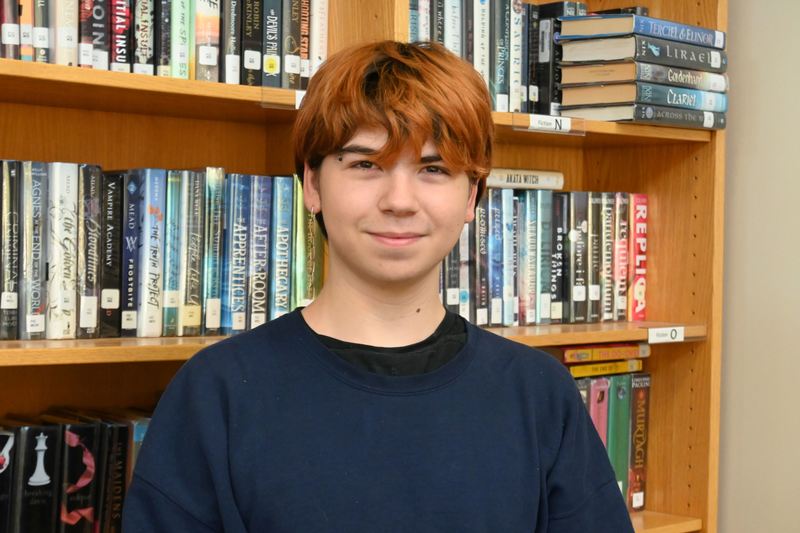

“The book talks about a lot of the cases they went through, and I was interested,” said junior Payton Corbett. “I looked into it and did a little research at the time because I didn’t know if I wanted to go down the lawyer path or the psychologist’s path. I learned a lot about EJI and what they fight for, and most of the cases they take on.”

Corbett said he’s always eager to learn “about anything and everything,” and that if he gets a chance to talk to someone experienced in a field he’s interested in, he wants to “soak up all the information” he can.

“What made me reach out is, I’m in the C.A.M.P. Club, and we learn about the uncensored history of a lot of different races and backgrounds that the textbooks don’t tell you about because it’s too graphic,” he said. “But I think it’s important to know those things no matter what. So, I figured, why not reach out to an organization that actually works on this stuff—fights for these people, goes through the legal process—and learn from them?”

Corbett shared his idea with C.A.M.P. Club sponsor Kristina Mayhue, telling her he wanted Bryan Stevenson to speak to the club. Mayhue praised the idea but told him it was up to him to make the contact.

With no direct contact information for Stevenson, Corbett decided to cast a wide net—sending emails to every address he could find, from EJI’s legal team to its social media accounts.

“I reached out to them, telling them what our club does, what I’m in it for, all that kind of stuff,” Corbett said. “I was hoping to reach Bryan Stevenson to have a Zoom or online meeting with him because I really liked his book, and a lot of my peers did as well.”

More than anything, Corbett hoped to learn more about Stevenson’s background and what led him to create EJI and write Just Mercy.

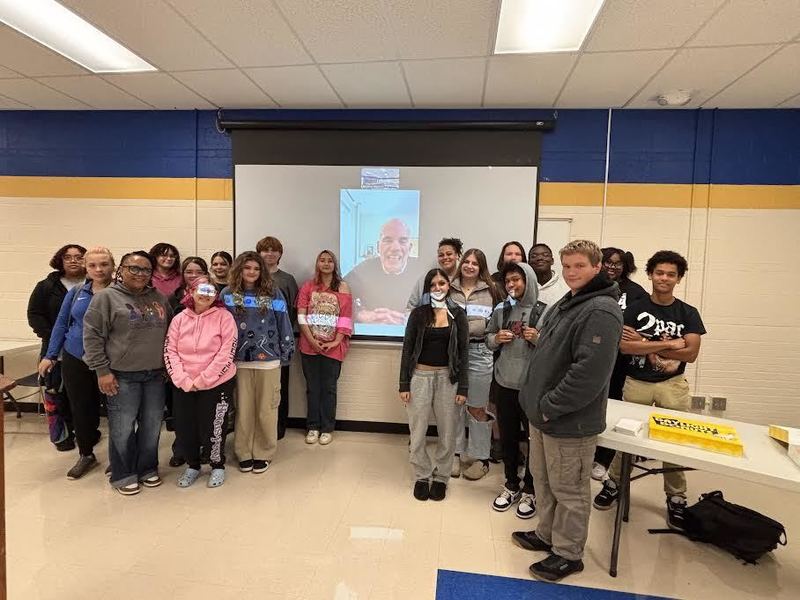

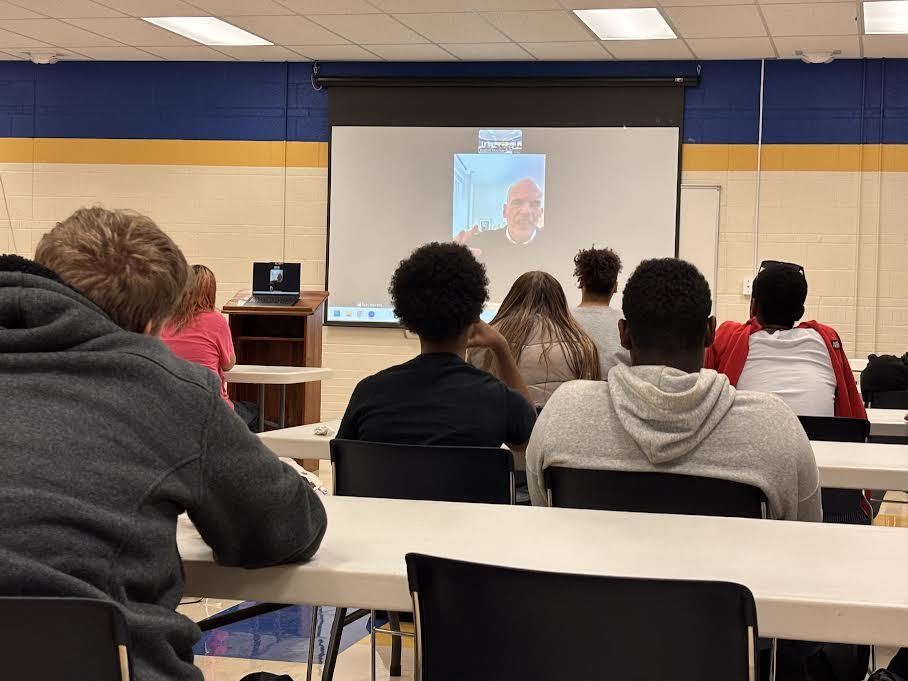

Before long, EJI Learning and Engagement Specialist Tad Roach contacted Mayhue and Corbett to coordinate a presentation via Zoom. Roach’s goal: to share more about Stevenson, EJI’s mission, and to inspire students to continue the work of addressing disparities that persist in the justice system.

“I was really excited and surprised about it,” Corbett said. “I was hoping someone would reach out but wasn’t getting my hopes up too high in case they said, ‘We can’t do an interview.’”

“It’s a big deal,” Mayhue said of EJI’s presentation to PHS students.

On Friday morning, Roach shared Stevenson’s story—from his childhood in 1950s Delaware, growing up in a segregated community, to being raised by parents who instilled a deep understanding of his ancestors’ struggles and resilience. Those early lessons in discrimination, intolerance, and injustice shaped Stevenson’s journey to becoming a lawyer and founding the Equal Justice Initiative.

Students also learned about the United States’ high incarceration rate—the highest in the world—and how the number of incarcerated people grew from 300,000 in the 1970s to more than 2 million by 2000, with a disproportionate number being Black and/or lacking resources for competent legal defense.

They heard about children being tried as adults, some even sentenced to death, and EJI’s fight to change those laws.

Roach shared stories that deeply impacted Stevenson, such as that of Anthony Ray Hinton, who spent 30 years on death row for a crime he didn’t commit. Fifteen of those years were lost to the justice system’s refusal to rehear his case—even after new evidence proved his innocence. EJI eventually took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which allowed Hinton to be exonerated..

Roach noted one of Stevenson’s well-known observations: “In America, it’s better to be rich and guilty than poor and innocent.”

Returning to the theme of hope at the end of his presentation, Roach encouraged students to believe in their potential to make meaningful change, just as Stevenson has.

“You are capable of extraordinary work,” he said.

Corbett said he was thrilled with the opportunity they were given and hopes Roach will return next year to share more.

“I think people should educate themselves if they really want to learn about history and make a lasting impact,” Corbett said. “There’s so much misinformation today, and people are susceptible to just believing it. Look into these organizations, look into these topics. If you actually care, you should be actively researching and helping fix the system—or the products of the system.”

Corbett plans to do just that. He hopes to major in psychology and minor in philosophy, ultimately earning a doctorate in psychiatry.

“The law system is really interesting to me, but I see how broken it is—even before doing my own research,” he said. If he weren’t so interested in psychology, he said, he would pursue law to try to fix those issues.

“But I figured, why not help the people who are affected by the issues? People can try to fix the broken machine all they want, but there are always going to be thousands stomping on the machine while you’re trying to fix it. So why not fix the byproducts of the machine? Fix the things affected—and then go for the main system. That’s what made me choose psychology over law, because I want to help people.”

“I’m really proud of Payton,” Mayhue said. “I want him to continue, because in our group we talk about leadership, confidence, and communication—all of those things, along with a sense of history—that I want them to take away from being in the club.”